Posts Tagged ‘Connecticut’

February 25, 2012

I’m not the most sophisticated naturalist in the world. I know some some birds, wildflowers and some science around living things,but I see myself as more of a carnival barker for nature. What I really want to do is shout, “Hey look at that, isn’t that neat? Here’s WHY!” I think in my line of work a certain ignorance may be a plus, which is obviously why my employer seems to be happy with my work. What I mean is it’s tough to get charged up about Acalypa Rhomboidea. But the common name Green Adder’s Mouth sounds mysterious and sexy. If you follow that salacious moniker up with the fact that it’s an endangered plant and not a dirty movie, an orchid growing 4-10 inches tall with miniscule flowers well- camouflaged by color that blossoms from June to August, well, cheeks may color with interest. (Folks blush about orchids more readily these days anyway, after that movie with Meryl Streep, The Orchid Thief.) So I use common names, not the Latin, when I go walking with groups. What I want is for people to (quite literally) catch the nature bug. They may catch it from me, and then go far beyond. I try to be as infectious as possible. Nature is important.

I’m not the most sophisticated naturalist in the world. I know some some birds, wildflowers and some science around living things,but I see myself as more of a carnival barker for nature. What I really want to do is shout, “Hey look at that, isn’t that neat? Here’s WHY!” I think in my line of work a certain ignorance may be a plus, which is obviously why my employer seems to be happy with my work. What I mean is it’s tough to get charged up about Acalypa Rhomboidea. But the common name Green Adder’s Mouth sounds mysterious and sexy. If you follow that salacious moniker up with the fact that it’s an endangered plant and not a dirty movie, an orchid growing 4-10 inches tall with miniscule flowers well- camouflaged by color that blossoms from June to August, well, cheeks may color with interest. (Folks blush about orchids more readily these days anyway, after that movie with Meryl Streep, The Orchid Thief.) So I use common names, not the Latin, when I go walking with groups. What I want is for people to (quite literally) catch the nature bug. They may catch it from me, and then go far beyond. I try to be as infectious as possible. Nature is important.

I’m not a scientist. But I sure am enthusiastic about the science of nature. It seems my I’ve spent my life walking outside and saying “What the heck is that?” Unable to leave the question unanswered, over the years I’ve scoured books and (these days) websites, gone to museums, and bought innumerable field guides in order to achieve a certain intimacy with the natural world. I’m comfortable there, and to a degree I see how it all goes together and why one thing needs another. Interdependence is a fundamental element of life. As humans we are included in that. And I think everyone ought to know it. So I’m shouting it out in my simple terms, the ones that most of us understand and grasp more viscerally.

I really wish they would stop teaching about the rain forest in elementary school classrooms. Don’t get me wrong, I find the rain forest as fascinating as anyone, and I worry about it a lot. But that’s why I want them to stop scaring the little kids about it. It’s pretty hard to teach about the rain forest without mentioning that it’s going to be a housing development before the children graduate from college. Why bother being excited about nature when there’s no point? That’s the lesson kids take away. Better to save the rainforest for middle and high schoolers and let them exercise some critical thinking on its problems. Instead, get the younger kids outside right here in their own environment. Show them how exciting their native forest is by letting them handle frogs and bugs, find crickets, catch fireflies, do the bee dance, learn their wildflowers. What we have here is as thrilling as the nature found all over the planet.

I really wish they would stop teaching about the rain forest in elementary school classrooms. Don’t get me wrong, I find the rain forest as fascinating as anyone, and I worry about it a lot. But that’s why I want them to stop scaring the little kids about it. It’s pretty hard to teach about the rain forest without mentioning that it’s going to be a housing development before the children graduate from college. Why bother being excited about nature when there’s no point? That’s the lesson kids take away. Better to save the rainforest for middle and high schoolers and let them exercise some critical thinking on its problems. Instead, get the younger kids outside right here in their own environment. Show them how exciting their native forest is by letting them handle frogs and bugs, find crickets, catch fireflies, do the bee dance, learn their wildflowers. What we have here is as thrilling as the nature found all over the planet.

I’m lucky. I have Hill-Stead Museum’s woodland, wetland and meadows with which to dazzle visitors. In a simple way I can show off the exciting nature of environment. In our 152 acres there is enough titillation for the  jaded. We even have rare orchids.

jaded. We even have rare orchids.

See you on the trails,

Diane Tucker, Estate Naturalist

Tags:Connecticut, elementary school classrooms, environmental education, museums, natural history, Nature

Posted in environment, hiking, museums, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, outdoors, Uncategorized, walking, wildlife | 15 Comments »

August 4, 2011

If I see another kid stomp on a bug during a nature walk, or scream and flail his arms around when he sees a bee I will lose my mind. And that’s only the children. You’d never believe some of the wacky things adults do on nature walks, like the school teacher who screamed and ran away and out of sight leaving 25 astonished third-graders with me and a sleeping garter snake we had just found under a bug board. Or the dozens of people you see going down into the Grand Canyon in high heels. But it’s little wonder when you consider how disconnected from life in the outdoors we are. Most people who attend nature hikes are unschooled in basic natural science and history. Many parents view nature hikes as strictly an entertainment for children, or for a springtime “science-lite” field trip from school with a hidden hijinks agenda.

If I see another kid stomp on a bug during a nature walk, or scream and flail his arms around when he sees a bee I will lose my mind. And that’s only the children. You’d never believe some of the wacky things adults do on nature walks, like the school teacher who screamed and ran away and out of sight leaving 25 astonished third-graders with me and a sleeping garter snake we had just found under a bug board. Or the dozens of people you see going down into the Grand Canyon in high heels. But it’s little wonder when you consider how disconnected from life in the outdoors we are. Most people who attend nature hikes are unschooled in basic natural science and history. Many parents view nature hikes as strictly an entertainment for children, or for a springtime “science-lite” field trip from school with a hidden hijinks agenda.

But we have some little successes. Two weekends ago I had a completely bug-phobic mother bring her children to “moth night”, our annual evening event when I bait trees and set up black lights to bring in moths and other night insects so they can be seen up close. You have to love a heroic parent like that, but to her surprise and mine she had a blast. Last weekend, I had kids and adults out in our meadow munching like happy cows on Queen Anne’s Lace roots, and arguing over the last bits. Just in case you aren’t on any of the very worthy survivalist list serves around, Queen Anne’s Lace is the cousin of the carrot and the roots smell quite alike. In darkness you’d be hard pressed to tell them apart. But the QAL tastes like an old, woody carrot, not a fresh one.

But we have some little successes. Two weekends ago I had a completely bug-phobic mother bring her children to “moth night”, our annual evening event when I bait trees and set up black lights to bring in moths and other night insects so they can be seen up close. You have to love a heroic parent like that, but to her surprise and mine she had a blast. Last weekend, I had kids and adults out in our meadow munching like happy cows on Queen Anne’s Lace roots, and arguing over the last bits. Just in case you aren’t on any of the very worthy survivalist list serves around, Queen Anne’s Lace is the cousin of the carrot and the roots smell quite alike. In darkness you’d be hard pressed to tell them apart. But the QAL tastes like an old, woody carrot, not a fresh one.

Looking over our meadows at Hill-Stead there are loads of wildflowers keeping Queen Anne and her lace company right now. Joe Pye Weed and Goldenrod are starting up, Black-Eyed Susan and Milkweed have been around a few weeks. The clover has been blooming for months. Clover, a member of the pea or legume family, grows in white, pink (often called “red”), and yellow (called “hop”), as well as a fuzzy, ochre-colored one called “rabbit’s foot”. If your yard had clover, a “good” yard service would advise you to eradicate it with pesticides. Aside from the pretty colors and the near continuous blooming habit, here’s why you might consider a stay of execution.

been blooming for months. Clover, a member of the pea or legume family, grows in white, pink (often called “red”), and yellow (called “hop”), as well as a fuzzy, ochre-colored one called “rabbit’s foot”. If your yard had clover, a “good” yard service would advise you to eradicate it with pesticides. Aside from the pretty colors and the near continuous blooming habit, here’s why you might consider a stay of execution.

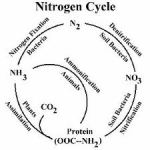

Nitrogen. Essential for life, it’s in about 80% of the air you breathe and is called “free nitrogen”, though it’s anything but free to us since we can’t directly use the airborne variety. Only “fixed nitrogen” is available to animals and plants. Where do we get it? Plants need nitrogen in the form of either nitrates or ammonia. These come from the soil, where they are dissolved in soil water, are taken up by the roots of the plants and start wending their way through the food chain. But, how do the nitrates and ammonia get into the soil? Nitrogen is “fixed”, or converted from free nitrogen in the air to nitrates (or ammonia) in various ways. Of course, people can add nitrogen to soil in the form of fertilizer. And lightening can cause reactions which result in the creation of nitrates. There is also “nitrogen fixing bacteria” that converts free nitrogen from the atmosphere into a useable form. The bacteria have enzymes that cause the change. Here’s where the clover comes in. The bacteria live in nodules on the roots of leguminous plants,-yes! Plants like clover, with both good looks AND talent.

Nitrogen. Essential for life, it’s in about 80% of the air you breathe and is called “free nitrogen”, though it’s anything but free to us since we can’t directly use the airborne variety. Only “fixed nitrogen” is available to animals and plants. Where do we get it? Plants need nitrogen in the form of either nitrates or ammonia. These come from the soil, where they are dissolved in soil water, are taken up by the roots of the plants and start wending their way through the food chain. But, how do the nitrates and ammonia get into the soil? Nitrogen is “fixed”, or converted from free nitrogen in the air to nitrates (or ammonia) in various ways. Of course, people can add nitrogen to soil in the form of fertilizer. And lightening can cause reactions which result in the creation of nitrates. There is also “nitrogen fixing bacteria” that converts free nitrogen from the atmosphere into a useable form. The bacteria have enzymes that cause the change. Here’s where the clover comes in. The bacteria live in nodules on the roots of leguminous plants,-yes! Plants like clover, with both good looks AND talent.

In short, clover unlocks a key to the entire food chain. I love it, and I keep what I have growing in my yard. Our meadows here at Hill-Stead are filled to the brim with clover-fixed-nitrogen and the food chain to go with it. I love showing it off to visitors. I don’t think that nature walks need to be treated as just a Sunday afternoon diversion for the kids, yet I don’t need everyone to be a citizen scientist, either. I would like for guests to come away from our programs with a fresh understanding of the outdoors, one that sees the human individual as part of the natural continuum, a steward and caretaker and, in fact, a party to the food chain itself. You don’t have to know the ins and outs of the nitrogen cycle for that. But you do have to go outside once in a while and look at the clover.

In short, clover unlocks a key to the entire food chain. I love it, and I keep what I have growing in my yard. Our meadows here at Hill-Stead are filled to the brim with clover-fixed-nitrogen and the food chain to go with it. I love showing it off to visitors. I don’t think that nature walks need to be treated as just a Sunday afternoon diversion for the kids, yet I don’t need everyone to be a citizen scientist, either. I would like for guests to come away from our programs with a fresh understanding of the outdoors, one that sees the human individual as part of the natural continuum, a steward and caretaker and, in fact, a party to the food chain itself. You don’t have to know the ins and outs of the nitrogen cycle for that. But you do have to go outside once in a while and look at the clover.

Tags:children and nature, Connecticut, ecology, environment, hiking, Hill-Stead Museum, insects, museums, natural history, Nature, outdoors, plants, Uncategorized, walking, wildflowers, wildlife

Posted in Connecticut nature, Conservation, environment, museums, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, outdoors, plants, rabbit, Uncategorized, wildflowers, wildlife | 13 Comments »

March 27, 2011

Some of my friends are on a “cleanse”. You need the book to participate- $9.16 on Amazon.com. You give up “obstacles to digestion” which apparently include eggs, nuts, dairy, tomatoes, eggplant, potatoes, peppers, meat, soy, cheese, wheat, and coffee. Since this doesn’t leave a lot you can actually eat, there is a line of shakes and supplements, $425 for the most popular package. Evidently people are contaminated with poisons from a diet which presumably includes tomatoes and peppers (see above list for other possibilities), and it is recommended that the cleanse continue for at least a month. If you have had the habit of eating any “allergen, mucous-forming or inflammatory” foods (see above), then you need to take and stay on a pre-cleanse program for a time before you can get into the actual cleansing. The more poisonous your previous diet, the longer the pre-cleanse. Then comes the gastrointestinal scrubbing during which you will need to take pills with names like Clear, Equilibrium, Pass, Ease and so on. The image I got when I heard about these wasn’t good at all, especially “pass” and “ease”.

Some of my friends are on a “cleanse”. You need the book to participate- $9.16 on Amazon.com. You give up “obstacles to digestion” which apparently include eggs, nuts, dairy, tomatoes, eggplant, potatoes, peppers, meat, soy, cheese, wheat, and coffee. Since this doesn’t leave a lot you can actually eat, there is a line of shakes and supplements, $425 for the most popular package. Evidently people are contaminated with poisons from a diet which presumably includes tomatoes and peppers (see above list for other possibilities), and it is recommended that the cleanse continue for at least a month. If you have had the habit of eating any “allergen, mucous-forming or inflammatory” foods (see above), then you need to take and stay on a pre-cleanse program for a time before you can get into the actual cleansing. The more poisonous your previous diet, the longer the pre-cleanse. Then comes the gastrointestinal scrubbing during which you will need to take pills with names like Clear, Equilibrium, Pass, Ease and so on. The image I got when I heard about these wasn’t good at all, especially “pass” and “ease”.

When you complete the tour of duty, you will feel energy and clarity, and be at least $434.16 lighter. Starvation for the privileged. But if you want to be on the cutting edge of weight loss fashion, look no further. The book alone is a runaway bestseller.

I am polite about all this. But I shudder at the frivolity while people the world over could eat for months on $425 and feel overfed. Being riven with hunger is torture. Real starvation means the Cheezits aren’t six feet away in the cabinet if you tire of it. The price of such hunger far exceeds $425. It is known, tragically, by millions.

On another plane, but no less pitiable is the deprivation known this winter by animals and birds throughout our area. As the snow melted here at Hill-Stead I sadly found quite a number of bird and animal corpses. In a harsh winter, hunger is a ruthless creditor.

This year birds gobbled up late summer berries like wild grape, pokeweed, poison ivy and blueberries before the fall was even over, so they had to start in on winter berries early. Winter berries include cedar, sumac and winterberry. They were in turn eaten up early. Starvation set in and with no other crop to draw from, many birds switched to eating alien and ornamental plants like multiflora rose and bittersweet. Without these foods as sustenance, I would have found quite a few more corpses during my springtime wanderings. This got me thinking. Because the birds had to switch over to eating invasive plants , it may mean that invasives will spread more than usual when spring warms up and the seeds dispersed by the birds begin to grow.

This year birds gobbled up late summer berries like wild grape, pokeweed, poison ivy and blueberries before the fall was even over, so they had to start in on winter berries early. Winter berries include cedar, sumac and winterberry. They were in turn eaten up early. Starvation set in and with no other crop to draw from, many birds switched to eating alien and ornamental plants like multiflora rose and bittersweet. Without these foods as sustenance, I would have found quite a few more corpses during my springtime wanderings. This got me thinking. Because the birds had to switch over to eating invasive plants , it may mean that invasives will spread more than usual when spring warms up and the seeds dispersed by the birds begin to grow.

I began to consider the further effect of an increase in alien plants. I’ll use Hill-Stead’s experience with a butterfly, the Baltimore Checkerspot, as the perfect example. This insect has a favorite food. And like a picky child, if the favorite food is unavailable it simply won’t eat. But the bug has more gumption than most children, and it dies out in places where its’ preferred plant has died out. No plant, no bug. In this way, once common insects become more local then gradually go extinct. Hill-Stead used to be a last gasp location for the Baltimore Checkerspot since we had quite a bit of turtlehead, the favorite plant. But the meadow began to be mowed in wider and wider margins, and the turtlehead went. It was long before my time and anyone else here now. But the butterfly census folks still shake their heads, and so do I. The Baltimore Checkerspot is not unique in its stubbornness. Every single insect is the same.

I began to consider the further effect of an increase in alien plants. I’ll use Hill-Stead’s experience with a butterfly, the Baltimore Checkerspot, as the perfect example. This insect has a favorite food. And like a picky child, if the favorite food is unavailable it simply won’t eat. But the bug has more gumption than most children, and it dies out in places where its’ preferred plant has died out. No plant, no bug. In this way, once common insects become more local then gradually go extinct. Hill-Stead used to be a last gasp location for the Baltimore Checkerspot since we had quite a bit of turtlehead, the favorite plant. But the meadow began to be mowed in wider and wider margins, and the turtlehead went. It was long before my time and anyone else here now. But the butterfly census folks still shake their heads, and so do I. The Baltimore Checkerspot is not unique in its stubbornness. Every single insect is the same.

But here’s the thing: 96% of terrestrial birds (as opposed to sea-going birds, for example) feed their babies on insects and spiders. What determines how many and what kind of insects are around? Plants! So, if we keep creating scenarios where invasives multiply, we will continue on a crash course with insect extinction and by extension bird extinction and by further extension, well, you get the idea.

Eastern Redbud (native)

Now it probably isn’t anyone’s specific fault that we had a bad winter and the birds had

Serviceberry (native)

to resort to eating multiflora rose hips. But it is our fault if we fail to increase our use of native species when we plant around our homes, parks and ornamental gardens. In this way, the birds and insects and everything that depends on them will have a leg up by having the proper food to eat. More native plants, more insects, more birds. More, please.

See you on the trails,

Diane Tucker

Estate Naturalist

Tags:birds, butterflies, Connecticut, Conservation, ecology, environment, hiking, Hill-Stead Museum, insects, invasive plants, natural history, Nature, outdoors, plants, sustainability, trees, Uncategorized, walking, wildflowers, wildlife

Posted in birds, bugs, butterflies, Conservation, environment, hiking, insects, invertebrates, museums, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, outdoors, plants, spiders, sustainability, trees, Uncategorized, walking, wildflowers, wildlife | 7 Comments »

March 10, 2011

It’s been a bitter winter. Record snow and ice, roofs collapsing day after day, kids home while crews shovel mountain-loads of snow off the school roof. After a beating like that, I have a hard time lifting my head and getting on with it. I am not a winter person. I do my best to enjoy it, adding snow shoeing to my repertoire of sports, but this winter I only made it out once and I lost my car keys in the snow. After that I wound up like a meadow vole, ten pounds of snow overhead, living alone in my own sub-nivean world. Now I’m struggling out of my lair, looking for a reason to stay above ground.

It’s been a bitter winter. Record snow and ice, roofs collapsing day after day, kids home while crews shovel mountain-loads of snow off the school roof. After a beating like that, I have a hard time lifting my head and getting on with it. I am not a winter person. I do my best to enjoy it, adding snow shoeing to my repertoire of sports, but this winter I only made it out once and I lost my car keys in the snow. After that I wound up like a meadow vole, ten pounds of snow overhead, living alone in my own sub-nivean world. Now I’m struggling out of my lair, looking for a reason to stay above ground.

I saw a mosquito yesterday, though temperatures were barely in the 40’s. He must have woken from diapause, that state of suspended animation that insects enter in the fall as days shorten. In diapause you are just about nearly dead, and I think that free-flying mosquito and I are in nearly the same situation right now.

Soon we should start seeing an occasional Mourning Cloak butterfly floating along. These guys are the Magellans of the butterfly world, first out to explore. They over-winter as adults too, and venture forth when the days are still relatively cool. Look for them, about the size of a four-year-old’s fist, rich brown with a creamy edge all around. When I think of them, I think of possibly getting out of my armchair. I’d hate to miss them.

As the snow melts, it’s a shock to see what’s been going on outside. When the layers recede, we see a winter’s tale of survival by those who cannot enter diapause. Mammals don’t have this option. So what do we see that reveals their winter lives and rituals?  Footprints are preserved in ice, sometimes new ones appear in the moist snow overnight. We know there were rabbits here earlier this winter. Did they make it? Food was scarce, plants were covered. Deer had the same problem and even coyotes started to feel the pinch. In fact, there were loads of animal sightings in crazy places this winter as predators were forced to make bold to find food, any food at all. Owls revealed themselves in frantic efforts to locate mice, moles and voles, all hidden tidily under three feet of snow. No chance to hear a telltale rustle and soundlessly pounce out of the sky. Rehabbers reported a record number of emaciated owls brought in for nursing. A friend tells me bears are out now, and another has seen a bobcat, so things are easing. And that’s especially good news for animals enduring winter without a snug den.

Footprints are preserved in ice, sometimes new ones appear in the moist snow overnight. We know there were rabbits here earlier this winter. Did they make it? Food was scarce, plants were covered. Deer had the same problem and even coyotes started to feel the pinch. In fact, there were loads of animal sightings in crazy places this winter as predators were forced to make bold to find food, any food at all. Owls revealed themselves in frantic efforts to locate mice, moles and voles, all hidden tidily under three feet of snow. No chance to hear a telltale rustle and soundlessly pounce out of the sky. Rehabbers reported a record number of emaciated owls brought in for nursing. A friend tells me bears are out now, and another has seen a bobcat, so things are easing. And that’s especially good news for animals enduring winter without a snug den.

As dog owners can tell you, there are a few other things exposed by snow melt. No,not dog toys! There is frozen scat everywhere. Personally, I am thrilled. The educational value of poop is not to be underestimated. Nothing gets a kid’s attention like poop. And let’s be honest, grownups tend not to forget that part of the nature walk, either, though possibly due to delicate sensibility rather than potty fascination. Coprology, the science of scatology, is a biggie. You can tell which animal did what. Size, shape and composition are nature’s mug shot. And it provides essential information about the diet of animals in a given area, their health and which diseases if any, are present. Tapeworm, anyone? Included in the package (pun intended) is information about where the animal has been and whether populations are rising or falling.

I better get out there before it all melts.

See you out on the trails,

Diane Tucker

Estate Naturalist

Tags:Connecticut, coprology, environment, hiking, Hill-Stead Museum, museums, Nature, New England, outdoors, Seasons, Uncategorized, walking, wildlife

Posted in Connecticut nature, Conservation, environment, hiking, insects, mammals, museums, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, outdoors, Uncategorized, walking, wildlife | 4 Comments »

December 21, 2010

What does it really mean to come home? Traffic projections tell us that this holiday season more people than ever will head home, possibly breaking a record for pre-Christmas travel. People across Europe lately find themselves stranded in airports from freak snowstorms, sleeping on the floor for days just trying to get where they wanted to go. Yet there are a gaggle of “funny” movies about going home for the holidays, especially Christmas, that depict the annual pilgrimage as nothing short of a personal horror. Sneering, taunting, insensitivity all play roles in such films and you have to wonder why anyone would ever go home to families like these. The answer of course is that they likely wouldn’t and the whole thing is just a device of “entertainment”. Sure, we laugh, but sometimes it’s an uncomfortable snicker. We recognize in them the subtle torture that only your loved ones can mete out.

What does it really mean to come home? Traffic projections tell us that this holiday season more people than ever will head home, possibly breaking a record for pre-Christmas travel. People across Europe lately find themselves stranded in airports from freak snowstorms, sleeping on the floor for days just trying to get where they wanted to go. Yet there are a gaggle of “funny” movies about going home for the holidays, especially Christmas, that depict the annual pilgrimage as nothing short of a personal horror. Sneering, taunting, insensitivity all play roles in such films and you have to wonder why anyone would ever go home to families like these. The answer of course is that they likely wouldn’t and the whole thing is just a device of “entertainment”. Sure, we laugh, but sometimes it’s an uncomfortable snicker. We recognize in them the subtle torture that only your loved ones can mete out.

Animals go home because they have to. It’s instinct and survival. Increasingly scientists are discovering that at some point living things across the spectrum from insect to mammal migrate from where they moved, returning to their original birthplace. Sometimes they go to breed, sometimes to die. It’s just built in. There is a lot unknown about animal interactions and in my sophomoric mind I wonder whether the outliers get made fun of when they turn back up with something new and different about them. In people, sometimes just maturing becomes rich fodder for family members to pick at, never mind a funny haircut or strange girlfriend. Good times!

There is a lot unknown about animal interactions and in my sophomoric mind I wonder whether the outliers get made fun of when they turn back up with something new and different about them. In people, sometimes just maturing becomes rich fodder for family members to pick at, never mind a funny haircut or strange girlfriend. Good times!

Mostly animals hunker down in winter, either hibernating or limiting their appearances to warmer winter days. The ones with really nice winter coats get around well, but even they need somewhere snug to see out a storm. Around here it’s pretty easy to see where our animal friends are hanging out. Because Hill-Stead’s grounds are still to my mind underused given the treasure they are, it’s a piece of cake to take a short walk and see deer tracks, coyote, our “famous” mink and loads of other creatures’ travels through snow and across the pond. You may even see one of the critters themselves.

But these darkest days of winter and indeed other dismal times, have a way of making us focus inward. Illness, loss, upheaval, have a way of isolating us whether or not we are even aware of it. To the best of my knowledge animals don’t have the luxury of introspection. They have to get on with it, just manage or pay the highest price. In contrast to us, they don’t go home for holidays or because they are worried and careworn. They can’t take umbrage at the modern world, hop on a train and go home to warm welcome and hot soup. It’s down the rabbit hole for them and hope for the best.

But these darkest days of winter and indeed other dismal times, have a way of making us focus inward. Illness, loss, upheaval, have a way of isolating us whether or not we are even aware of it. To the best of my knowledge animals don’t have the luxury of introspection. They have to get on with it, just manage or pay the highest price. In contrast to us, they don’t go home for holidays or because they are worried and careworn. They can’t take umbrage at the modern world, hop on a train and go home to warm welcome and hot soup. It’s down the rabbit hole for them and hope for the best.

Wherever you go, or if you go anywhere at all, everyone here at Hill-Stead hopes you find yourself someplace cozy and restful.

Happy Holidays, and I’ll see you on the trails,

Diane Tucker

Estate Naturalist

Tags:animals, Connecticut, Hill-Stead Museum, holidays, Nature, outdoors, Uncategorized, wildlife

Posted in Connecticut nature, environment, hiking, history, museums, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, outdoors, Uncategorized, walking, wildlife | 2 Comments »

August 2, 2010

I see it every time I drive down Mountain Road to Hill-Stead. It’s the Tree of Heaven, officially known as Ailanthus altissima. Originating in China, it is mentioned in ancient dictionaries and medical texts and was used there to cure everything from mental illness to baldness. Today it’s still used in traditional Chinese medicine, principally as an astringent. Like lots of invasive plants and animals, Ailanthus grows fast and soon dominates the landscape. In an extremely un-heavenly move, it sends chemicals into the ground to discourage growth around it so it can suck up all the surrounding resources and stretch unimpeded toward the sun. You can find Ailanthus anywhere the land has been disturbed and some say it has a real stink to it, like the female Ginko tree.

Our Tree of Heaven is located near the spot where a wooly mammoth was pulled from a bog by Hill-Stead farm workers in 1902. For a time it was the “must see” for scientists from all over, as it was then the first completely intact skeleton ever found. One of the biggest archeological finds of its time, it even helped popularize the word “mammoth”. The Tree of Heaven couldn’t have been there in 1902 since at that time the whole area was part of the Pope farm. But when Theodate died her will dictated that Hill-Stead should become a museum. There just wasn’t enough money from her estate (the bulk of which went to the Avon Old Farms School, which she founded and for which she designed the buildings) to create a museum. So they sold 100 acres of land, which included the Wooly Mammoth bog and the place where the Tree of Heaven sits now. But I still think of it as “our” land. I have no doubt that if Theodate had known the value open spaces would come to have, she would have written her will differently. Now the area is dotted with homes (some brand new as the area continues to grow) and a tennis club. Having been bulldozed by developers I think the property qualifies as “disturbed”, so no one should be surprised that this behemoth of a tree has grown there in such a short time. Many invasive plants and wildflowers are found in such places. An Ailanthus can reach 49 ft within 25 years or so.

Our Tree of Heaven is located near the spot where a wooly mammoth was pulled from a bog by Hill-Stead farm workers in 1902. For a time it was the “must see” for scientists from all over, as it was then the first completely intact skeleton ever found. One of the biggest archeological finds of its time, it even helped popularize the word “mammoth”. The Tree of Heaven couldn’t have been there in 1902 since at that time the whole area was part of the Pope farm. But when Theodate died her will dictated that Hill-Stead should become a museum. There just wasn’t enough money from her estate (the bulk of which went to the Avon Old Farms School, which she founded and for which she designed the buildings) to create a museum. So they sold 100 acres of land, which included the Wooly Mammoth bog and the place where the Tree of Heaven sits now. But I still think of it as “our” land. I have no doubt that if Theodate had known the value open spaces would come to have, she would have written her will differently. Now the area is dotted with homes (some brand new as the area continues to grow) and a tennis club. Having been bulldozed by developers I think the property qualifies as “disturbed”, so no one should be surprised that this behemoth of a tree has grown there in such a short time. Many invasive plants and wildflowers are found in such places. An Ailanthus can reach 49 ft within 25 years or so.

I think the tree is pretty. It has large compound leaves at least a foot long, with between 10 and 41 leaflets each. At this time of year it flowers,and the cultivar we happen to have becomes flame-colored . You can see it from from a long way off. Tree of Heaven has determination, reproducing not only by seed, but also by throwing up “suckers” all around it through the earth. It can withstand dirt, dust, pollution of every kind and still it pulls itself up toward the sun. Tree of Heaven was the inspiration for the book “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” by Betty Smith, and it is easy to see why.

I think the tree is pretty. It has large compound leaves at least a foot long, with between 10 and 41 leaflets each. At this time of year it flowers,and the cultivar we happen to have becomes flame-colored . You can see it from from a long way off. Tree of Heaven has determination, reproducing not only by seed, but also by throwing up “suckers” all around it through the earth. It can withstand dirt, dust, pollution of every kind and still it pulls itself up toward the sun. Tree of Heaven was the inspiration for the book “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” by Betty Smith, and it is easy to see why.

“A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” tells the story of Francie Nolan, who lives in poverty in Brooklyn, New York. Like so many immigrants at the turn of the last century, the family struggles to attain a piece of the American dream. Francie’s mother feels the key to this is a good education and she is determined her children will have one. A Tree of Heaven grows in a vacant lot near their apartment and symbolizes the determination of the family to rise above their circumstances. It is a wonderful book-a real touchstone for millions of people. It was adapted to a movie and a stage play, no doubt because the story is a familiar one to Americans whose backgrounds include many a Francie Nolan.

“A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” tells the story of Francie Nolan, who lives in poverty in Brooklyn, New York. Like so many immigrants at the turn of the last century, the family struggles to attain a piece of the American dream. Francie’s mother feels the key to this is a good education and she is determined her children will have one. A Tree of Heaven grows in a vacant lot near their apartment and symbolizes the determination of the family to rise above their circumstances. It is a wonderful book-a real touchstone for millions of people. It was adapted to a movie and a stage play, no doubt because the story is a familiar one to Americans whose backgrounds include many a Francie Nolan.

What a contrast to Theodate Pope, daughter of one of the richest families in America! She came from Cleveland to Farmington to attend one of the most elite schools in the country,- a far cry from Francie Nolan, who yearned for any education at all, to save her from a lifetime of scrubbing floors. And yet in her own way, Theodate was swimming against the courant, too. Unlike her peers, she wanted a farm and a career, an unseemly, unusual aspiration for a young girl with means. Her mother couldn’t understand it and they were at odds. Theodate and Francie were not dissimilar in their yearning for that which was just nearly out of reach to them. Their goals were close enough to tantalize, yet odd enough to be hard to realize within their specific social castes.

What would life be without the thirst for something more? I bet most people driving down Mountain Road in Farmington don’t notice our tree even when it blooms. But I am just as certain that they each have a personal Tree of Heaven within them.

What would life be without the thirst for something more? I bet most people driving down Mountain Road in Farmington don’t notice our tree even when it blooms. But I am just as certain that they each have a personal Tree of Heaven within them.

Tags:Connecticut, environment, Hill-Stead Museum, invasive plants, Miss Porter's School, Nature, outdoors, plants, trees, Uncategorized

Posted in Connecticut nature, environment, history, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, plants, trees, Uncategorized | 5 Comments »

July 17, 2010

To market, to market to buy a fat pig, home again, home again jiggedy jig!

I used to think of myself as a farmer’s market connoisseur, since I’ve been a devotee of them long before the “eat local” craze happened. I trolled around markets in Vermont, driving my edible booty home to Connecticut in my back seat. Once on the cutting edge of fashion, now I don’t even have to leave Farmington for my weekly organic kibble. I can just stroll over to Hill-Stead Museum with my reusable sack over my arm. The trend for farmer’s markets is growing fast. There are urban farms, urban markets, country farms and country markets. They are thick on the ground in trendy suburbs. We need many more. It seems evident that an important key to restoring all manner of food integrity is local farming. In a sense, we are harvesting our food tradition to sow a food future. And it’s not just some la-di-dah keeping up with the Jones kind of food trend, either. You could argue that the value of recycling our food culture is fundamental to our long-term well-being, both at the stove and elsewhere, and is reflective of something organic in ourselves.

I used to think of myself as a farmer’s market connoisseur, since I’ve been a devotee of them long before the “eat local” craze happened. I trolled around markets in Vermont, driving my edible booty home to Connecticut in my back seat. Once on the cutting edge of fashion, now I don’t even have to leave Farmington for my weekly organic kibble. I can just stroll over to Hill-Stead Museum with my reusable sack over my arm. The trend for farmer’s markets is growing fast. There are urban farms, urban markets, country farms and country markets. They are thick on the ground in trendy suburbs. We need many more. It seems evident that an important key to restoring all manner of food integrity is local farming. In a sense, we are harvesting our food tradition to sow a food future. And it’s not just some la-di-dah keeping up with the Jones kind of food trend, either. You could argue that the value of recycling our food culture is fundamental to our long-term well-being, both at the stove and elsewhere, and is reflective of something organic in ourselves.

“Well-being” isn’t what prompts us to visit a farmer’s market. Rather, it is almost as though there is a part of our cultural DNA that has been wanting for decades, to get us back to the activity of “market day”. What would Thomas Hardy be without them? Many a plot is turned in the market square of literature. Think of Jane Austen, George Eliot, The Brontes, Mrs. Gaskell. There are today markets held all over Europe throughout the year, whereas most of ours, for now at least, seem to be summertime phenomena. Why do so many of us get so excited about about a few stands of vegetables and flowers popping up in the same location up every seven days? Why have some cultures never left off doing it?

“Well-being” isn’t what prompts us to visit a farmer’s market. Rather, it is almost as though there is a part of our cultural DNA that has been wanting for decades, to get us back to the activity of “market day”. What would Thomas Hardy be without them? Many a plot is turned in the market square of literature. Think of Jane Austen, George Eliot, The Brontes, Mrs. Gaskell. There are today markets held all over Europe throughout the year, whereas most of ours, for now at least, seem to be summertime phenomena. Why do so many of us get so excited about about a few stands of vegetables and flowers popping up in the same location up every seven days? Why have some cultures never left off doing it?

A farmer’s market provides a “front porch” for a culture that has sadly grown away from such things. We see neighbors, offer tips to strangers about how to use an unfamiliar vegetable, embrace a fondly remembered farmer. Mr. Bingley bows deeply there to Miss Bennet. As so often also happens at the Hill-Stead poetry festival, one hears happy whoops of recognition punctuating the atmosphere as we see old friends. We begin to make new relationships, too. The crowd is heterogeneous, and thus community is made, not just among a few select neighbors, but in a town and region.

A farmer’s market provides a “front porch” for a culture that has sadly grown away from such things. We see neighbors, offer tips to strangers about how to use an unfamiliar vegetable, embrace a fondly remembered farmer. Mr. Bingley bows deeply there to Miss Bennet. As so often also happens at the Hill-Stead poetry festival, one hears happy whoops of recognition punctuating the atmosphere as we see old friends. We begin to make new relationships, too. The crowd is heterogeneous, and thus community is made, not just among a few select neighbors, but in a town and region.

A farmer’s market turns us toward one another, emphasizing our fundamental interdependence on the level of comestible and emotional sustenance. There are other organic connections we cannot name. Joining together over food is perhaps the oldest form of community, save for procreation itself. Earthiness is, as it turns out, a great leveler.

Join us this Sunday and every Sunday until October 24, 11am-2pm, rain or shine. Beyond the vegetables, you’ll find quite a lot that is special. Enjoy companionship, hear music, get community information at our tent, pet a farm animal, drink a coffee or simply enjoy the atmosphere. After you’re done with that, take a walk on one of the historic trails. For a small fee, go inside the house and see rare art and glimpse a lost lifestyle.

Join us this Sunday and every Sunday until October 24, 11am-2pm, rain or shine. Beyond the vegetables, you’ll find quite a lot that is special. Enjoy companionship, hear music, get community information at our tent, pet a farm animal, drink a coffee or simply enjoy the atmosphere. After you’re done with that, take a walk on one of the historic trails. For a small fee, go inside the house and see rare art and glimpse a lost lifestyle.

For more information on our website: http://hillstead.org/activities/farmersmarket.html

And look for me, I’ll be there. Or, I’ll see you on the trails,

Diane Tucker

Estate Naturalist

Tags:Connecticut, Conservation, environment, farmer's markets, Farming, Food, hiking, Hill-Stead Museum, locavore, Nature, outdoors, Sunken Garden Poetry Festival, sustainable produce, Uncategorized, walking

Posted in Connecticut nature, Conservation, environment, farming, history, locavore, museums, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, outdoors, plants, sustainability, Uncategorized, walking | 6 Comments »

June 24, 2010

I had a nice time last night at Hill-Stead Museum’s Sunken Garden Poetry Festival. How could you not? It was a perfect summer evening. Latin flavored jazz filled the air while picnics were shared, wine poured, blankets fluffed out over the lush grass. The Sunken Garden itself was in all its June glory, the Summer House providing the backdrop for the music and for the reading of poems. Now and then a little cry of happy recognition flared up as friends found one another in the gloaming.

I had a nice time last night at Hill-Stead Museum’s Sunken Garden Poetry Festival. How could you not? It was a perfect summer evening. Latin flavored jazz filled the air while picnics were shared, wine poured, blankets fluffed out over the lush grass. The Sunken Garden itself was in all its June glory, the Summer House providing the backdrop for the music and for the reading of poems. Now and then a little cry of happy recognition flared up as friends found one another in the gloaming.

Our Beatrix Farrand-designed sunken garden played host to two fine poets, Gabrielle Calvocoressi and Bessie Reyna. What a treat it was. And as the sunset turned into night, birds flew to roost and night time things began to take over. I was happy to see several chimney swifts, as I did last year. And the wager still stands that they have nests in church steeples here in Farmington. Other than raising young, the swifts live the entirety of their lives on the wing, and it may be that they dip their wings at us bi-weekly while we admire our nationally-known poets. One lone bat skittered across the sky, looking uncoordinated, but being actually anything but.

The full list of the attendees were as follows:

Red-Tailed Hawk

European Starling

American Robin

Catbird

American Goldfinch

Chipping Sparrow

Chimney Swift

Song Sparrow

American Crow

Downy Woodpecker

Tufted Titmouse

Eastern Bluebird

Wood Thrush

Brown-Headed Cowbird

Tree Swallow

Blue Jay

Eastern Phoebe

White-Breasted Nuthatch

Coopers Hawk

Hermit Thrush

Red-Eyed Vireo

Cardinal

Grackle

Great Blue Heron

Shetland Sheep

1 Dragonfly

1 bat

Field Crickets

Fireflies

Tree Toads

Other than the hundreds of people, there were 24 species of bird, 3 species of insect, 1 amphibian, 1 bat, a small flock of literary critic Shetland Sheep, a slightly more than three-quarter moon and Saturn glowing in the early summer sky. And poetry. There was lots of that. Define it how you like.

See you on the trails,

Diane Tucker

Estate Naturalist

Tags:amphibians, bats, birds, Connecticut, Connecticut Tourism, environment, Hill-Stead Museum, insects, museums, Nature, outdoors, Poetry, Sunken Garden Poetry Festival, Uncategorized, wildlife

Posted in Connecticut nature, museums, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, Poetry, Uncategorized | 12 Comments »

May 28, 2010

After my mother died, I saw her everywhere. I followed people whose hair reminded me of hers before shaking off the idea that it might somehow be her. This kind of reaction is completely normal, and in a way comforting after a loss, but I never expected to feel similarly about a few muskrats.

Earlier this year I thought I saw a weasel of some kind around the pond, and one day I got a good view. It was a mink. They are very handsome animals, and I don’t think most people think of them as weasels although they are a member of the same family. They think of them as coats. Weasels, of course, have a bad reputation and it isn’t nice to call someone a weasel, or be called one yourself. The insult is intended to mean “sneaky and low-down”. Weasels are also considered (by farmers especially) to be cruel and needless killers. Because they often “scalp” their prey and simply leave it, people think that the weasel kills for sport. Not so-he kills and returns later to eat the prize. He’s not fussy about a little putrification, and he also “caches” his food. A farmer who wakes to a hen house full of scalped chickens regards the weasel as the worst kind of varmint, and the natural history of it is of little importance to him. But a weasel has to kill when the opportunity presents itself, and also have a little something to fall back on. You never know when a meal is going to come along and a mink has a high metabolism. Think of them as the Holly Golightly of the animal world. And I think I remember that Holly Golightly had a really nice mink coat.

Earlier this year I thought I saw a weasel of some kind around the pond, and one day I got a good view. It was a mink. They are very handsome animals, and I don’t think most people think of them as weasels although they are a member of the same family. They think of them as coats. Weasels, of course, have a bad reputation and it isn’t nice to call someone a weasel, or be called one yourself. The insult is intended to mean “sneaky and low-down”. Weasels are also considered (by farmers especially) to be cruel and needless killers. Because they often “scalp” their prey and simply leave it, people think that the weasel kills for sport. Not so-he kills and returns later to eat the prize. He’s not fussy about a little putrification, and he also “caches” his food. A farmer who wakes to a hen house full of scalped chickens regards the weasel as the worst kind of varmint, and the natural history of it is of little importance to him. But a weasel has to kill when the opportunity presents itself, and also have a little something to fall back on. You never know when a meal is going to come along and a mink has a high metabolism. Think of them as the Holly Golightly of the animal world. And I think I remember that Holly Golightly had a really nice mink coat.

Minks are solitary, except during breeding, at which time they virtually define the word “promiscuous”, with both males and females mating as much as possible, with as many partners as possible. So the gene pool is nice and healthy, and the DNA for survival very strong. These animals are smart and canny predators, eating fish torpid from cold during winter and switching to slower, more defenseless animals in warm weather. Which brings me back to the muskrats. Mink will eat anything, but they really love muskrat. Also, “abandoned” muskrat lodges make swell mink houses. So I think it is pretty clear what happened to the Hill-Stead muskrat family. Of course, muskrats need water that covers them. Our pond is getting more shallow all the time, so the muskrat days were numbered in any case.

Minks are solitary, except during breeding, at which time they virtually define the word “promiscuous”, with both males and females mating as much as possible, with as many partners as possible. So the gene pool is nice and healthy, and the DNA for survival very strong. These animals are smart and canny predators, eating fish torpid from cold during winter and switching to slower, more defenseless animals in warm weather. Which brings me back to the muskrats. Mink will eat anything, but they really love muskrat. Also, “abandoned” muskrat lodges make swell mink houses. So I think it is pretty clear what happened to the Hill-Stead muskrat family. Of course, muskrats need water that covers them. Our pond is getting more shallow all the time, so the muskrat days were numbered in any case.

For a while, I saw the muskrats in my imagination, too. But, as with my mother, I finally had to accept that they were gone. In the hierarchy of small mammals, the mink with its sensitive nose and killer instinct has it all over the poor vegetarian muskrat, who just likes to noodle around the pond eating weeds. And even in the hierarchy of coats, the mink is the trophy outerwear, the muskrat for wannabe’s.

But nature has a way of equalizing things, and the mink may eventually be taken by a coyote or even an owl. And then I’ll miss the mink.

Tags:Connecticut, ecology, environment, hiking, mammals, Nature, outdoors, Uncategorized, walking, wildlife

Posted in Connecticut nature, Conservation, environment, hiking, mammals, natural history, Nature, New England Museums, outdoors, Uncategorized, walking, wildlife | 8 Comments »

May 12, 2010

There are so many things that need saving it can really be demoralizing. Whales, wolves, panthers, funny little owls, hundreds of songbirds, frogs. The list is endless. All you have to do is say the word “rainforest” and you summon up images of destruction. It’s why I don’t believe in teaching elementary kids about the rainforest at all. Let them enjoy the pleasure of nature and develop a love for it, before you discourage them with tales of extinction and despair. That people think the only interesting nature exists thousands of miles away, really only demonstrates the need for education about local natural history. There is a fascinating backstory everywhere you look, no matter where you look.

There are so many things that need saving it can really be demoralizing. Whales, wolves, panthers, funny little owls, hundreds of songbirds, frogs. The list is endless. All you have to do is say the word “rainforest” and you summon up images of destruction. It’s why I don’t believe in teaching elementary kids about the rainforest at all. Let them enjoy the pleasure of nature and develop a love for it, before you discourage them with tales of extinction and despair. That people think the only interesting nature exists thousands of miles away, really only demonstrates the need for education about local natural history. There is a fascinating backstory everywhere you look, no matter where you look.

The American Kestrel is a bird in need of intervention. It depends on areas of grassland, and so is getting squeezed out of survival by the minute. Instead of farms with fields, we now have either forests or building sites, so things are tough for grassland birds like grasshopper sparrows, woodcock, upland sandpipers, meadowlarks, kestrels and others.

The American Kestrel is a tiny falcon that resembles its larger cousin the Peregrine, only with a swankier color scheme. It has blue, cream,

The American Kestrel is a tiny falcon that resembles its larger cousin the Peregrine, only with a swankier color scheme. It has blue, cream, black and rusty shades of feathers, along with stripes beneath the eyes that cut down on the glare during high-speed chases after fleeing prey. All the better to see you with, my dear. The female of the species is color-wise a little more subdued, the better to remain camouflaged as she sits on a nest.

black and rusty shades of feathers, along with stripes beneath the eyes that cut down on the glare during high-speed chases after fleeing prey. All the better to see you with, my dear. The female of the species is color-wise a little more subdued, the better to remain camouflaged as she sits on a nest.

Perched on a fence, nest box or other spot overlooking the meadow, a kestrel darts off to snatch prey out of the air. In that way, it resembles a flycatcher. But it has the ability to hover in the air scanning the area and adjusting its trajectory before diving out of the glare like a Kamikaze pilot. The hovering would make you think of a hummingbird. Because the kestrel is diminutive in comparison to just about every other bird of prey, from far off it isn’t too hard to believe you are looking at a hummer, but only for a moment. Kestrels are about the size of a robin, and the hovering behavior is a great skill. Some people still refer to the kestrel as a “sparrow hawk” (I can’t help thinking of Foghorn Leghorn and his precocious sidekick here), from its ability to take down smaller birds.

Kestrels are faithful, both to a mate, and to a nesting place. Research on one pair showed that they returned to the same nesting spot for six years. It is a remarkable statistic, given that the bird has a mortality rate of nearly 50%. Kestrels themselves are frequently the prey of larger birds, and their own reproduction depends on the availability of cavities within which to make a nest.

that the bird has a mortality rate of nearly 50%. Kestrels themselves are frequently the prey of larger birds, and their own reproduction depends on the availability of cavities within which to make a nest.

They are well adapted to nest boxes, and this is where Hill-Stead and Art Gingert come in. Art is on a mission to save the American Kestrel. With a keen admiration for the little bird, a wide experience as a naturalist and a steady arm with a hammer, drill and ladder, Art is scouring the state for locations that might tempt the kestrel to nest in one of his specially-designed boxes. They are fashioned out of quality wood, and follow a design he has developed based on his long experience.

Art and I put a box up the other day in one of our meadows. One of Hill-Stead’s many claims to fame is the three full-sized elms that have managed to survive the ravages of Dutch Elm disease. One of them, and by far the prettiest in my opinion, sits out in one of our hay meadows. No other tree is near it and the eye is drawn automatically to its graceful form. A Kestrel would probably see it as easily as we do. At least, that is what we hope. Art carefully hung the box, even using a level to make sure the look of it was pleasing. Now all we have to do is attract the birds. It’s a gamble to be sure. There aren’t even that many Kestrels left, comparatively speaking, and it may be vain of us to imagine that one or two will happen along and notice our box.

But there is much to be said for preserving local treasures. Just ask some of those men and animals that used to live in the rainforest.

But there is much to be said for preserving local treasures. Just ask some of those men and animals that used to live in the rainforest.

See you on the trails,

Diane Tucker, Estate Naturalist

Tags:American Kestrel, birds, Connecticut, Conservation, ecology, environment, Nature, outdoors, Uncategorized, wildlife

Posted in birds, Connecticut nature, Conservation, environment, natural history, Nature, outdoors, Uncategorized, wildlife | 6 Comments »

I’m not the most sophisticated naturalist in the world. I know some some birds, wildflowers and some science around living things,but I see myself as more of a carnival barker for nature. What I really want to do is shout, “Hey look at that, isn’t that neat? Here’s WHY!” I think in my line of work a certain ignorance may be a plus, which is obviously why my employer seems to be happy with my work. What I mean is it’s tough to get charged up about Acalypa Rhomboidea. But the common name Green Adder’s Mouth sounds mysterious and sexy. If you follow that salacious moniker up with the fact that it’s an endangered plant and not a dirty movie, an orchid growing 4-10 inches tall with miniscule flowers well- camouflaged by color that blossoms from June to August, well, cheeks may color with interest. (Folks blush about orchids more readily these days anyway, after that movie with Meryl Streep, The Orchid Thief.) So I use common names, not the Latin, when I go walking with groups. What I want is for people to (quite literally) catch the nature bug. They may catch it from me, and then go far beyond. I try to be as infectious as possible. Nature is important.

I’m not the most sophisticated naturalist in the world. I know some some birds, wildflowers and some science around living things,but I see myself as more of a carnival barker for nature. What I really want to do is shout, “Hey look at that, isn’t that neat? Here’s WHY!” I think in my line of work a certain ignorance may be a plus, which is obviously why my employer seems to be happy with my work. What I mean is it’s tough to get charged up about Acalypa Rhomboidea. But the common name Green Adder’s Mouth sounds mysterious and sexy. If you follow that salacious moniker up with the fact that it’s an endangered plant and not a dirty movie, an orchid growing 4-10 inches tall with miniscule flowers well- camouflaged by color that blossoms from June to August, well, cheeks may color with interest. (Folks blush about orchids more readily these days anyway, after that movie with Meryl Streep, The Orchid Thief.) So I use common names, not the Latin, when I go walking with groups. What I want is for people to (quite literally) catch the nature bug. They may catch it from me, and then go far beyond. I try to be as infectious as possible. Nature is important. I really wish they would stop teaching about the rain forest in elementary school classrooms. Don’t get me wrong, I find the rain forest as fascinating as anyone, and I worry about it a lot. But that’s why I want them to stop scaring the little kids about it. It’s pretty hard to teach about the rain forest without mentioning that it’s going to be a housing development before the children graduate from college. Why bother being excited about nature when there’s no point? That’s the lesson kids take away. Better to save the rainforest for middle and high schoolers and let them exercise some critical thinking on its problems. Instead, get the younger kids outside right here in their own environment. Show them how exciting their native forest is by letting them handle frogs and bugs, find crickets, catch fireflies, do the bee dance, learn their wildflowers. What we have here is as thrilling as the nature found all over the planet.

I really wish they would stop teaching about the rain forest in elementary school classrooms. Don’t get me wrong, I find the rain forest as fascinating as anyone, and I worry about it a lot. But that’s why I want them to stop scaring the little kids about it. It’s pretty hard to teach about the rain forest without mentioning that it’s going to be a housing development before the children graduate from college. Why bother being excited about nature when there’s no point? That’s the lesson kids take away. Better to save the rainforest for middle and high schoolers and let them exercise some critical thinking on its problems. Instead, get the younger kids outside right here in their own environment. Show them how exciting their native forest is by letting them handle frogs and bugs, find crickets, catch fireflies, do the bee dance, learn their wildflowers. What we have here is as thrilling as the nature found all over the planet. jaded. We even have rare orchids.

jaded. We even have rare orchids.